Last week I got an email from someone who’s been reading my stuff since it was a scattershot blog for the outdoor apparel company I used to own. I knew him as an avid trail runner, a peak bagger, a classic mountain enthusiast. But in this last email he admitted that was only half the picture. “I'm a slave to corporate America,” he said. “I do it for my wife and kids, and resentment eats at my soul much worse than the nightly beers eat at my liver and kidneys. But their toll will come...”

His words refused to leave my mind.

On that old blog I used to write stuff like this: See, we, rock climbers, are rebels in a world that wants to cut off our hair and sell us a suit. We turn our back on the idea that $$$ is more than a means to an end. Because we know it’s not about the material things we have, but what we do with those things that matters.

The truth was, though, at that time I also worked in a cubicle compiling title documents for a mortgage company. However, I didn’t write about this side of my life—why talk about something in which you experience little pride, right?—so when this longtime reader offered such unfettered openness about his predicament, I had to lean into his honesty.

I asked for an interview. And he agreed to go deeper. (And I, in turn, agreed to keep it anonymous for obvious reasons.)

So sit back . . . as we explore the modern-day fight between freedom and expectation through the eyes of someone who’s given 30 years to the corporate world, how we all sometimes wind up inside circumstances we never imagined—and how we might yet escape.

ASCENDING THE LADDER

Tell us what you do . . .

I am a manager of a customer service team for a brokerage firm. The accounts we service may hold all types of securities (mutual funds, bonds, ETFs, stocks, options) and besides handling incoming calls and emails, my team is also tasked with making outbound proactive communications.

How did you get yourself into this position?

I've been working in corporate America for nearly 30 years. As a young newly-wed a year out of college, I just needed to find work. With a BA in English and not being very handy, I wasn't going to be a carpenter or plumber.

It started as a temp job sorting mail. Then I got a full-time offer to join a department that was mostly data entry with some phones. The phones were terrible: long hold times to reach firms you needed information from, incoming calls from irate customers upset about fees or delays. But that job landed me the opportunity for a research position, where I got paid way more to put up with those irate callers, and actually felt some satisfaction in solving their problems.

What promise did you buy into when joining the corporate world?

I bought the classic American Dream. That working diligently effectively translated to upward mobility. At my first company, progress seemed easy: in the course of two years, I nearly doubled my laughable income tosomething comfortable, and found myself striving for new roles. Generally it took 3-5 months to master each role, then I’d take a new one. It genuinely felt good to provide answers to customers and to help co-workers.

But soon enough I found myself drowning in work delegated to me by the supervisor, maybe a consequence of my persistence. I was newly divorced, so the long hours didn't bother me, the mental exertion becoming a welcome diversion from the emotional turmoil inside. The strain of overwork was drowned in Friday night happy hours that led to even later excursions to clubs with a co-worker or two. But the bonus paid by the company was more generous than any I'd ever experienced, so I kept going.

Did you ever question the corporate path in the beginning?

During those first years while I rose through the ranks, I had also enrolled in a graduate program in pursuit of the dream of becoming an English professor—but the prospect of driving across town to teach a class at this community college and that university, with no health benefits, and more schooling (a PhD to obtain) in order to be eligible for a full-time faculty position did not inspire me. I had a more interesting and financially rewarding career at hand.

I want to jump in here and relay a story about the corporate world which

shares in his newsletter from Adelle Waldman’s book Help Wanted. In the story “the savviest executive from the head office recognizes great talent in a lower-level executive. She knows that if he ever gets lured away from the retail industry by Wall Street or Private Equity, he will likely become extremely wealthy—seven, perhaps eight, figure income wealthy—so to lock him in place, she tells the loyal executive that he’s on a fast track to be promoted to positions that will eventually pay him a few multiples of the very low six figures he’s earning now. He’s delighted. He doesn’t realize his true earnings potential.”Obviously, no one can see with perfect clarity what lies down the line—we could all wind up broke soon enough—but there’s a particular maliciousness to a boss cajoling a promising employee to stay in their current role, intentionally kneecapping their potential. Although somehow this seems less surprising in the corporate universe when it’s direct reports all the way down.

Back to the interview . . .

DISILLUSION SETS IN

How long did the good times last before you realized the corporate gig wasn’t what you had imagined?

I’ve worked for three different Fortune 500 companies without ever leaving my business unit. The first time the company was sold, I found out from a co-worker looking at an online news article. Ten years later it happened again, only this time I was a manager—not that it mattered because still no one told me. And that’s when I understood the people working the ranks to make these large corporations flourish are just decimals on aspreadsheet.

You said earlier that resentment eats at your soul. What do you resent, exactly?

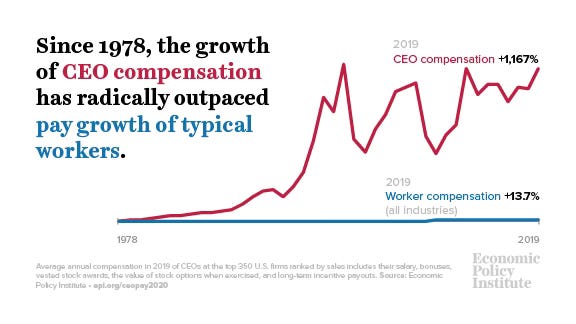

I resent the hypocrisy of the ultra-capitalist mission, coupled with the slick, well-applied veneer of humanism. The top executives continue to make more and more money, while the vast majority of employees spend year after year looking at a 2% raise. It's insane to think that the tax liability of some of these executives exceeds the salaries of those whom they employ.

Then something happens in the industry and the layoffs occur. Despite the continual feast and famine cycle oflabor, the work still needs to get done, and employees work long days, long weeks, giving up vacation time to make it happen.

Why would I do this? Well, I care about our customers and I take pride in my work. I want to be a person of integrity, someone others can rely upon, and there are all these excellent corporate values to spur me to do my best: BE CLIENT-CENTRIC, OWN IT, COLLABORATE. Yes, I truly believe in all these values but the demands are unsustainable. And the result is that the good people get burnt out over time and leave, making more work for those still around, and the spiral continues.

Why stay corporate then and not find a better-suited path for yourself?

It gets down to comfort, necessity. In my imagination, I always romanticize this idea of living free of material things, able to move on a moment's notice, ever-ready for adventure. But apartments are crowded, noisy places. And there is the dream of home ownership and the promise of the equity you get from it. I bought a townhome and then a house and accumulated stuff. Van life would appeal, but you can't raise kids that way, and it would never appeal to my wife, even if we didn't have kids.

What would it take for you to turn your back on the corporate world now?

I've been trying to figure this out. After my upcoming 30th anniversary of corporate work next year, I don't see any realistic means of leaving this world earlier than 2030, when our youngest son will graduate high school and I'll be 58 years old. For that to happen, either my wife will need to double her income or I'll need to find a second job in the interim (subject to approval by my corporate owner) to provide savings.

I've heard "follow your passion" but my passions are not lucrative. Mountain guides or park rangers don't make enough money to support three kids and a wife who also works part-time to balance family demands with her own career aspirations. And would I enjoy the mountains as much if I were having to cater to clients, make sure they are well-energized and hydrated, properly outfitted, etc.? I've always enjoyed writing, too, but the road to authorship is not a path to readily replacing daily wages.

So that leaves other business endeavors, nearly all of which would require new training or education, and starting back from the bottom.

LIVE TO WORK, WORK TO ESCAPE

So, how do you find a sense of escape?

For the past 20 years, my escape has been the mountains. Heck, I even dream about them—I was looking at a map of the San Juans one time and jarringly realized that I was looking for a mountain on the map that wasn't real. In my sleep, I've created a whole mythical sub-range to the east of the Grenadiers sub-range in the real world San Juans. Can you believe that?

What dreams does your corporate gig hold back? What would it take to attain them?

This is an important thing for young adults to think about. What do you want to do? Don't “settle down and get a job to save up for those big adventures to do later” because you might get to too old to do them.

Life is about choosing your opportunities. Each choice we make acts to open up new opportunities and simply removes others from the table. Now in my fifth decade, I realize that there are numerous mountaineeringexperiences I will not have—there is insufficient time and money available due to the choices I've made.

What would you tell someone considering a corporate job now?

I have a friend who is a very successful business owner. We started college together and he transferred after our sophomore year to obtain a specific degree at another college. It struck me at the time as rigid; I was living a fluid life of being present to the moment, happily drifting in a world of ideas and parties. But my friend was deliberate and decisive; he thought about what he wanted and did the research to figure out the best course to get it.

My career development has happened more organically, like how a tree grows, and that's a pretty metaphor but I don't think it works well for fulfillment. I think people need to think deeply about what experiences they want from life, what they want their everyday to be, what they want vacations to be, and milestones, what they want to do by 30, 40, etc. Then, prioritize those things. Figure out what you need to do to attain those visions—because what you have are goals and a goal without a plan is just a dream. Dreams go unrealized unless there is a plan, followed by actions to complete it.

Regularly revisit your dreams/goals, think about your current work, and deliberate on what changes you WANT to make, each year. Don't do it like I did, with regrets and self-loathing and new resolutions each January that go unfulfilled. Just set up a time to check on your plan monthly and make sure you are heading to where you want to be.

An old carpenter once told me that construction picks up the people who don’t fit in anywhere else. I’ll speak for myself (though I imagine it applies to all the carpenters and plumbers I work with) when I say I wouldn’t last one day in a cubicle anymore.

Nevertheless, there’s a sentiment I sometimes hear on the job, often accompanied by a shrug: work’s work. When it comes to putting food on the table and paying the bills, sure, work’s work. But if it’s never more than that, what’s the end result?

Does a job like that lead to satisfaction? Or maybe it provides just enough comfort find yourself 30 years down the line, questioning yourself only when it’s too late? I don’t necessarily have the answers—even if I did they’re probably not your answers, anyway.

But I’ll share something from writer Mark Manson on the state of our working lives:

The 20th century did not reward curiosity. The traditional structures of schools, corporations, and the church didn’t just deter open questioning and experimentation—they often feared it. Instead, they usually rewarded emulation. Any sort of innovation or experimentation was limited to a few people at the very top of the pyramid. Everyone else was expected to be a good worker bee.

But the internet has inverted this. Today, it seems that it's the ones who fail to experiment, innovate, or challenge preconceived notions who get left behind. The defining trait of progressing in the 21st century appears to be a driving curiosity about anything and everything.

It’s never too late to start being curious. Cultivate it. Who knows what might take root.

One final note: almost twenty years ago I quit school to hike the Appalachian trail. A lot of people thought I was crazy (for the record, I went back to school). Out there I met an older guy one day who’d set up camp for the night, though it was only lunch. As I did with most fellow hikers, I asked what had brought him to the trail.

“After forty years of working at the same desk, I had to do this.” Then he searched the sky for a moment, before looking me square in my teenaged-eye, adding: “Whatever you do, don’t go corporate.” With that he retired to his tent, leaving me alone in the middle of the woods, with a well-worn footpath before me.

Thanks again to my longtime reader for his openness and honesty.

-Martin

It seems to me that whatever path you choose, be intentional about it and know what the costs are

Why not just put work in its place?

Why does it HAVE to offer us meaning? Why does it HAVE to offer us daily joy and satisfaction?

Yes, there are better (and worse) ways.

But it seems to me we've put work too high on a pedestal and when we do, we're all bound for this type of disappointment.

P.S. I've been there too...